訪談:胡志穎裝置《安徒生童話》在紐約現代藝術博物館

Interview: Hu Zhiying’s Installation Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales Displayed in MoMA

訪談:胡志穎裝置《安徒生童話》在紐約現代藝術博物館

地點:紐約現代藝術博物館

時間:2016年4月18日

人物:胡志穎,藝術市場通訊

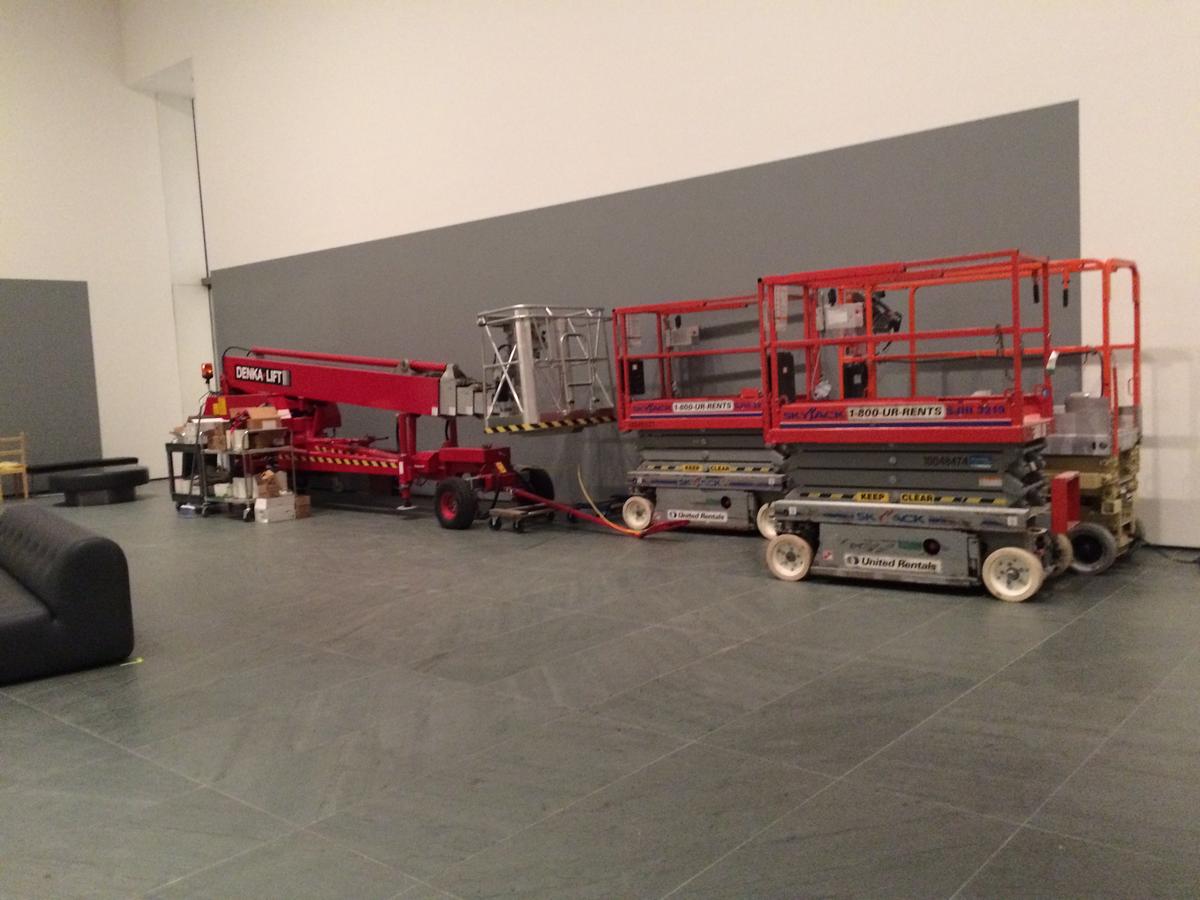

胡志穎 《安徒生童話》現場之一,2016,裝置,綜合媒介,紐約現代藝術博物館

HU ZHIYING The Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (1), 2016, Instalation, Mixed Media, New York Museum of Modern Art

藝術市場通訊(以下簡稱“藝”):胡志穎先生,您這次在紐約現代藝術博物館的裝置《安徒生童話》規模很大,您是怎樣構想和安裝這一系列作品的呢?

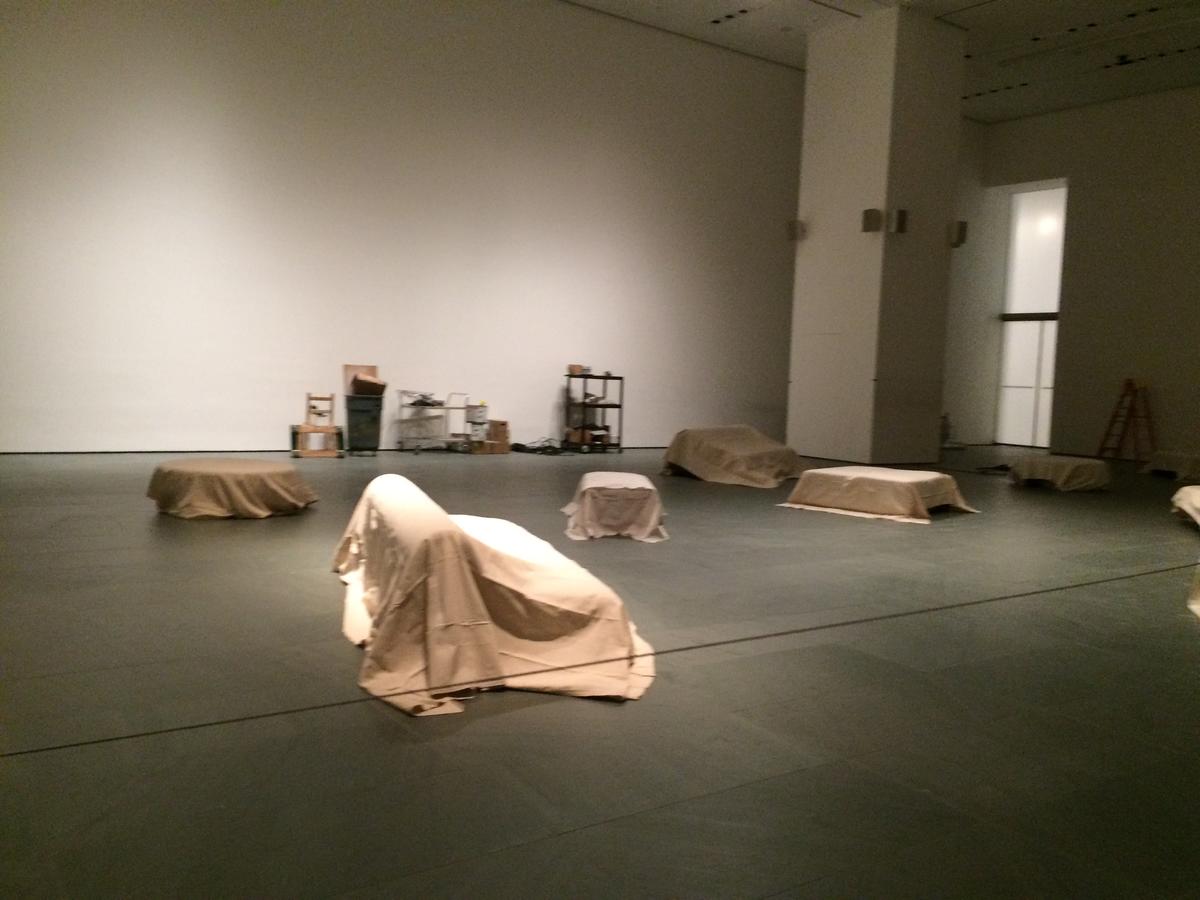

胡志穎(以下簡稱“胡”):展覽2016年2月12日開始裝置,2016年2月19日—4月18日展出。我的《安徒生童話》裝置佔據紐約現代博物館(MoMA)二樓整個主廳,由多種物件和媒介組成——形狀各異的沙發、數捆布匹、起重機、吊車、腳手架、木箱、鋼索、塑膠薄膜、水箱等等,看似各自為政的孤立,但又自成一個整體,不同於一般的形式,它既不是系列作品也不是單件作品,可以感覺到眾多的無數,也可以感覺一件都不是。《安徒生童話》裝置,獨一無二之處是,它始終處於動態之中。我在展覽期間的中途任意時間抽掉沙發上的布匹,又在任意時間再次覆蓋上布匹,每一次覆蓋布匹的形式也不一樣,沙發的位置也在變動,機器在移動……同一物件,但不同時間在不同位置……所以,聚光燈對有些作品(物件)是錯位的,而且不同時日的對位與錯位也在變化(可比較現場之一、之四)。

它沒有起點也沒有終點,又不是簡單的循環往復。它是一種變化不定的自然演變,故而物件是可移動的,數目是忽多忽少的,鬆散的,今天和明天又不一樣、不一致,它呈現的是自然現象,而非我們通常概念中的作品樣態。與我在以往廣州絹麻廠、罐頭廠的裝置《世紀遺恨錄》(室內和戶外)、廣州龍洞的裝置《新康得》(戶外)、華南植物園的裝置《無主的錘子》(室內)、廣州珠江夜晚船舶上的裝置《否定的辯證法》(戶外)等也有一定程度的呼應,這次《安徒生童話》是裝置在MoMA室內。

胡志穎《世紀遺恨錄》之二,2003,裝置,綜合材料,廣州絹麻廠

HU ZHIYING Century Remorse II, 2003, Instalation, Mixed Media, Guangzhou Silk and Linen Factory

胡志穎《世紀遺恨錄》之四,2003,裝置,綜合材料,廣州罐頭廠

HU ZHIYING Century Remorse IV, 2003, Instalation, Mixed Media, Guangzhou Canning Factory

藝:胡先生,我們知道,您以往的裝置作品大多是以廢棄的工廠為環境,也包括大型機器,瓦礫,布匹以及廢棄物,等等,藉此切入工業文明所包含的癥結以警世人,您這次在MoMA室內做大型裝置,物件和材料互有聯繫,您能介紹一下您是如何考量二者的內在關係和外在形式之間差異性的嗎?

胡:《安徒生童話》裝置,沿用了我在裝置上自1990年代以來的一貫美學傾向“自然美學”,這個所謂的“自然”不僅僅是傳統(包括現代藝術,業已成為傳統)的自然,就在於,我把自然看作“觀念-直覺性”的自然。要害並不在於工業文明的質疑或存在的問題之類,儘管觀者也可以這麼認為,紐約獨立策展人保羅·布裡奇沃特也持此觀點,而且實際上也已然包含著這個問題,但它似乎更是一種自然存在——自然狀態的自述和轉述(人工演化為天然)的混合,自然的自我呈現和表達的混合。也就是說,這個自然反映的出來的是我已經存在和滲透在其中的“自然”。工業文明下的機器連結、批量沙發、失去端點的布匹……都不是傳統意義上的自然,我們既生活在其中,卻無法厘清它們是廠房的物件還是居所的陳設還是荒野的遺棄物還是藝術品,因為它們幾乎無所不在,乃至於我們在現實中看到真實存在的幻覺,這種幻覺誕生於觀念-直覺性與實存之間,猶如置身現代文明交錯於共用與隔離的現代童話世界。

胡志穎 《新康德》(04),2012,裝置,綜合媒介,廣州龍洞

HU ZHIYING Neo-Kant (04), 2012, Instalation, Mixed Media, Longdong in Guangzhou

藝:您為什麼以“安徒生童話”命名這次在MoMA的大型裝置,它與安徒生的那一則童話有關聯?或者與兒童有什麼聯繫,或者是兒童的想像力有什麼聯繫嗎?

胡:看上去毫不相干的器物之間有沒有交流?它們真實地成為各自的角色而自然存在著。這些實實在在的器物恰恰生髮出某種難以言表的荒漠性,致使我們無法厘清現實(同時也是非現實)的真義而成為譫妄者,這種譫妄的幻覺自身就是以童話方式存在著的自然。安徒生童話的意念和結構具有童話世界的代表性,我的裝置《安徒生童話》並沒有具體對應哪一篇童話故事,它是童話世界的譫妄狀態。我常常從兒歌中聽出一種無以名狀的荒漠性感覺,而童話的想像力和兒童的想像力同樣具有與現實產生懸隔的譫妄性,但它卻是一種自然演化的存在。

藝:紐約作為國際藝術之都不僅雲集了來自世界各地的藝術家,也是全世界各國縱橫交替、川流不息的欲望之城,其影響力直接輻射全球。您能介紹一下您的《安徒生童話》裝置在紐約現代藝術博物館的展覽的現場情況嗎?

胡:饒有意味的是,這種荒漠性通過現場而再一次實證著它的荒漠性。通過現場照片可以看到二樓《安徒生童話》裝置前觀眾寥寥無幾,但其它藝術作品前的觀眾依然很多,紐約現代藝術博物館幾乎每天人潮湧動。所以,我的《安徒生童話》這件作品前的圍欄已經成為一種形式或者作為作品的一部分而存在,失去了通常圍欄的功能性作用和本意,人們漠視(或許視而不見)這些孤立于人類行為意志之外又為人們熱衷製造的人造物件。就像此前的《偽望遠鏡》、《世紀遺恨錄》、《新康得》、《否定的辯證法》被遺忘在廢棄的工廠裡、被擱置在荒野、遊弋在江海湖泊……這次在MoMA這種莊重的博物館安置《安徒生童話》裝置,既沒有突出的獨立於其他人物和事物的刻意性,又矗立為荒漠的孤寂,不管主體性的人是否在意這些自然狀態,也不論主體性的人的多少,都被這自然狀態不知不覺地所延伸演化為自然現象的存在。

胡志穎 《安徒生童話》現場之五,2016,裝置,綜合媒介,紐約現代藝術博物館

HU ZHIYING The Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (5), 2016, Instalation, Mixed Media, New York Museum of Modern Art

《安徒生童話》不是人們習慣的裝置形式,它裝置的方式是忽略面對觀眾,反過來也就必然導致觀眾的忽略,這種兩者的相互背離,更準確地說是相對而言的互不存在。 “互不存在”的結果是無視、無記憶、無謂的自然狀態。所以,觀眾不容易真正感受和認知到我的作品。我似乎已經習慣了一種不被認知、無法交流的自我抽身而走的行者的自由。

胡志穎《否定的辯證法》,2013,裝置,綜合媒介,廣州珠江夜晚船舶上

HU ZHIYING The Negative Dialectics, 2013, Instalation, Mixed Media, at Night on the Ship in Guangzhou Pearl River

藝:您認為藝術應該有意義嗎,或者可以無意義,或者在有意味和無意味之間?您的《安徒生童話》屬於哪一種?

胡:《安徒生童話》是否突破了“藝術是有意味的形式”這句前衛藝術的聖言?裝置《安徒生童話》與其說它的意義在於藝術陳述的勃勃雄心,還不如說它像征著自然演化的滄海一粟。我堅信人類具有無法分辨真實與虛幻、藝術與非藝術界限的天賦秉性,藝術家也不例外,過去、現在、未來都是如此。

(原載《 藝術市場通訊》2016年,《畫廊》雜誌2017年第九期)

Interview: Hu Zhiying’s Installation Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales Displayed in MoMA

Venue: Museum of Modern Art

Time: April 18th, 2016

Character: Mr. Hu Zhiying, Marketing Communication of Art

胡志穎 《安徒生童話》現場之六,2016,裝置,綜合媒介,紐約現代藝術博物館

HU ZHIYING The Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (6), 2016, Instalation, Mixed Media, New York Museum of Modern Art

Marketing Communication of Art (hereinafter referred to as “MCA”): As we can see, Mr. Hu, your installation art exhibition Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales was on a large scale. Could you tell us how you conceived and installed the whole series?

Hu Zhiying (hereinafter referred to as “Hu”): We started to install the work on February 12th, 2016, and displayed it during the period from February 19th to April 18th, 2016. My installation Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales took up the whole main hall on the second floor of Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which was consisted by various kinds of objects and media - different shapes of sofas, piece goods, cranes, hoists, scaffolds, wooden case, cable wires, plastic films, waste tank, etc. Each of them might seem to be isolated, but from a certain perspective, they formed an integral whole. It’s a special form that we could neither say it’s a serious nor a single work since spectators sometimes see the amount of it while sometimes feel it as nothing. Being always in a dynamic and active state was a unique feature of my installation Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales. During the exhibition, I repeatedly withdrew the clothes on the sofa randomly and then optionally replaced it with another piece of cloth. Every time I put different clothes there to replace the former one. Besides, the position of the sofa had been changed over and over again, so did the machine. There would definitely be different feelings towards the same object in different time and different positions. So, in fact, the spotlight was constantly changing its positions to create the different visual effect (you could compare the first part and the fourth part on the spot.)

胡志穎《新康德》(09,超級康德),2012,裝置,綜合媒介,廣州龍洞

HU ZHIYING Neo-Kant (09, Supper-Kant), 2012, Instalation, Mixed Media, Longdong in Guangzhou

There’s not any starting points or ending points for the whole work, and it’s not simply repeating. Instead, it’s fluctuating and transforming. Therefore, objects could be moved and their quantity could be changed. We could see different scenes on different days. And that’s why it was presenting spontaneously, totally different from what we expected in the concept of “artwork”. In addition, I did this also to echo my former installation works Century Remorse in Guangzhou Factory of Silk and Linen (outdoor) and Canning Factory (indoor), Neo-Kant in Longdong, Guangzhou (outdoor), Ownerless Hammer in South China Botanical Garden (indoor), and Negative Dialectics in the ship sailing in Pearl River at night (outdoor).

胡志穎《偽望遠鏡》所見之一,1992,裝置,不銹鋼,長130cm,直徑6.6cm

HU ZHIYING View 1 Seen Through the Pseudo-Telescope , 1992, Instalation, stainless steel, length 130 cm, diameter 6.6 cm

MCA: As we know, most of your former installation artworks were displayed in abandoned factories with large-scale machines, debris, clothes and other wastes so as to caution the common people to protect themselves from the sequel caused by industrial civilization. As per the large device in MoMA this time, objects are closely related to materials. Would you please give us an introduction of differences between the two factors both internally and externally?

Hu: In fact, I used the concept of “Natural Aesthetics”, which had always been said to be a consistent tendency of aesthetics since the 1990s, in the installation Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales. And in my word “natural” I didn’t mean only the natural tradition (including modern art), but also my natural instinct and professional art intuition. The crucial part was not the doubts about industrial civilization (although spectator might think so), but the natural existence - a combination of self-statement and paraphrase that had been made natural through artificial evolution, and a mixture of both self-presentation and expression. That is to say, the installation had presented a real “nature” state that I infiltrated in advance. So we can see that not any of the linkage of machines, a lot of sofas or the clothes without any endpoints were traditionally “natural” under the circumstance of industrial civilization. Although we are living in that atmosphere, we are still unable to figure out whether they are articles of a factory, or layouts of a residence, or abandoned materials in the wild, or actually a work of art because they are everywhere. Maybe it’s some illusions that are existed in real life, which was generated between intuitiveness and existence and made the modern civilization a fair tale world by both sharing and isolating.

胡志穎 《安徒生童話》現場之四,2016,裝置,綜合媒介,紐約現代藝術博物館

HU ZHIYING The Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (4), 2016, Instalation, Mixed Media, New York Museum of Modern Art

MCA: Why did you name this large-scale installation exhibition in MoMA as “Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales”? Did it have something to do with the fairy tales, with children, or with the imagination of children?

Hu: If you think there is not any communication among these objects that seem to be irrelevant, you’re wrong. As a matter of fact, they’re living their own characters and at the same time influencing others. And the offish aura they emit confused us by creating illusions so that we won’t be able to clarify the reality and finally become deliriants, just like the ways living in fairy tales. Stories in Andersen's Fairy Tales are actually good representatives of the fairy tale world, and that was why I named the exhibition like this. But my installation Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales didn’t particularly correspondent to anyone of the fairy tales. Instead, what it did was to present a delirious state of that wonderful world. I used to feel something indifferent when listening to children’s songs, and maybe that was because children are actually like fairy tales - both their imaginations have the ability to separate themselves from the reality. Nevertheless, it’s a natural evolution.

胡志穎 《安徒生童話》現場之二,2016,裝置,綜合媒介,紐約現代藝術博物館

HU ZHIYING The Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales (2), 2016, Instalation, Mixed Media, New York Museum of Modern Art

MCA: As an International city of art, New York always has the force to gather great artists from all over the world, and in fact, it’s also a city of desire for those who want to display talent. So we can say it is rooted in America and affecting the whole world. Since your exhibition was held in MoMA, could you tell us how it worked on the scene?

Hu: It’s meaningful that the apathy of spectators had once again reflected the apathy of the installation. We can see from the photos on the spot that there were very few people watching Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales while it was crowded before other artworks - as you know, it’s usual to see so many people in MoMA. Therefore, the rail in front of the work had also become a part of it, gradually losing its original function. All that was because people were disregarding these artificial things that they thought “shouldn’t be artworks” while in fact, they keen on making them themselves. Do you still remember my former works Pseudo-Telescope, Century Remorse, Neo-Kant and Negative Dialectics? They were forgotten and silently staying in the factory, in the wild, and even in the lake. And Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales was just like them. This time in MoMA, such a solemn place, my installation didn’t distinctly make itself independent from other artworks. Instead, it was naturally spreading the feeling of solitude no matter the spectators cared or not and no matter how many people were there. It was just there, naturally, like people’s routine.

The shape of Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales was not familiar to spectators since it chose to ignore them, which inevitably resulted in the ignorance of the spectators. The work and the people were departing from each other, or we can say, they see each other as a thing that was non-existent. Hence, both of them didn’t care any memories or states of each other. And that’s why it’s hard for people to truly feel and know my work. But I’ve got used to it - being unacknowledged and doing no communication. But I’m free, and I could just go away. I don’t care.

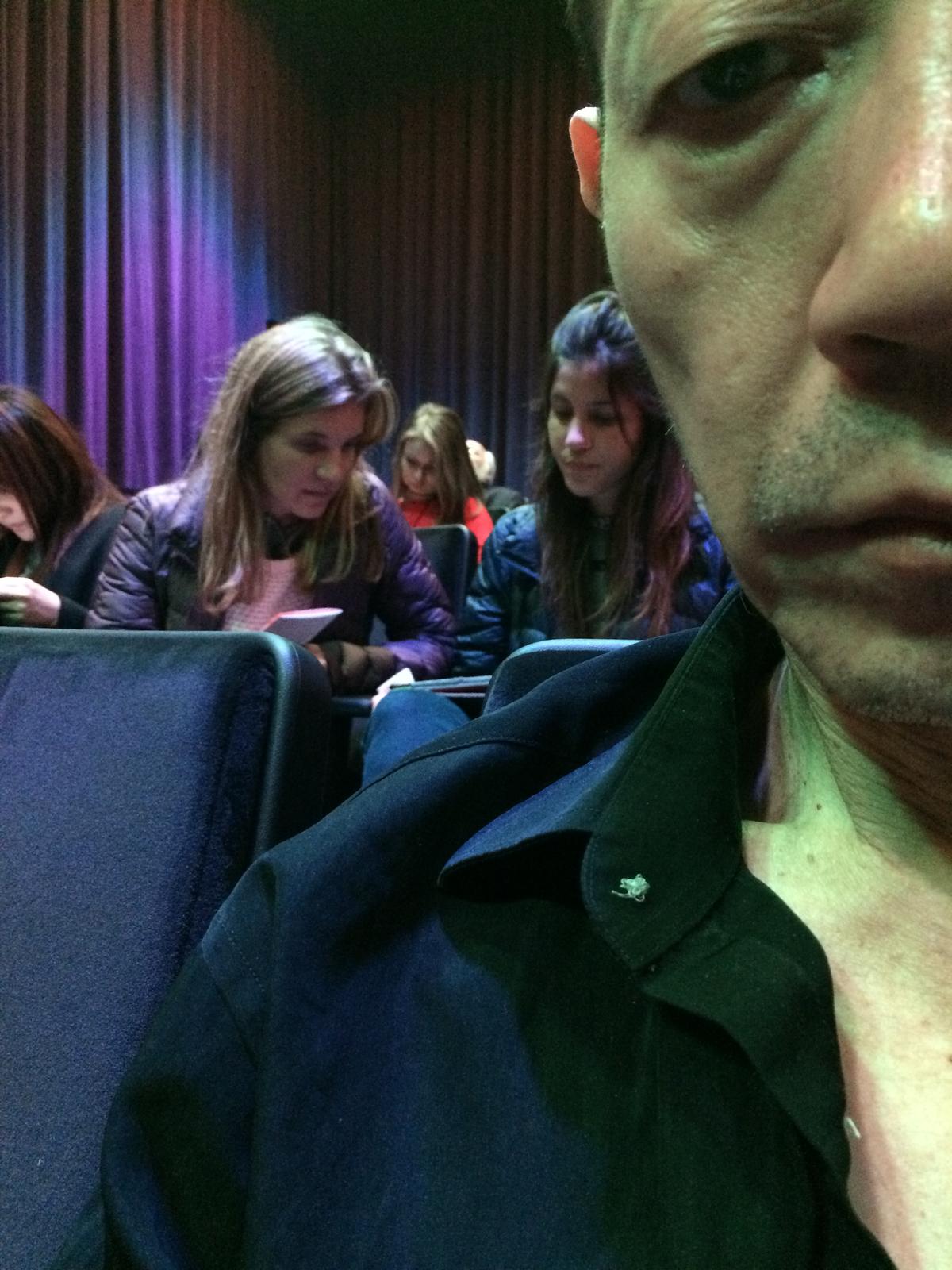

胡志穎 2016年在紐約現代藝術博物館電影播放館

HU ZHIYING in New York Museum of Modern Art in 2016

MCA: Do you think art should be meaningful or meaningless? Or could it be between the former and the latter? And which kind of meaning your work Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales belong to?

Hu: I don’t know whether Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales has surpassed the holy word of art that “Art is a meaningful pattern” or not, and I wouldn’t say its meaning lies on the ambition of art stating. Because I think it is a drop in the ocean that symbolizes the natural evolution. I firmly believe that human has a heaven-born gift that doesn't tell the boundary between truth and hypocrisy, and between art and non-art, even the artists. And I would say it is an iron law in the past, at present, and in the future.

published in Marketing Communication of Art, 2016

published in Gallery, 2017, No. 9